Over the past few years, in the race to combat climate change, electric cars have become an increasingly popular choice among drivers. However, they are not the only alternative to internal combustion cars that burn fossil fuels.

Hydrogen cars have seen some use as well, but what are they, how do they work, and will they really solve the issues fossil fuels and battery-powered electric vehicles have?

First, the science

Hydrogen cars come in two main flavours: hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles, and Fuel Cell Vehicles.

Hydrogen internal combustion engines work much like the fossil fuel engines we’re phasing out, but are adapted to burn hydrogen instead of fossil fuels, resulting in emissions being entirely water (assuming pure fuel). They have seen some use over the years, but are largely being phased out in favour of fuel cell vehicles.

By contrast, fuel cell vehicles work more like battery-powered electric vehicles. The main difference is that instead of a large lithium ion battery, the car has a compressed hydrogen tank which it then reacts with oxygen from the air to produce the electricity for the electric motors. They also commonly feature either a small battery or a supercapacitor to smooth out the current.

However, those are primarily implementation details. For the rest of the article you can assume either one as most points apply just as well to both.

Advantages

The main advantage over fossil fuels is that emissions from burning hydrogen are not toxic, it’s water, after all, but they’re otherwise about the same.

When put next to electric vehicles, however, the advantages are more noticeable. Refueling is faster because you just pump some hydrogen in a tank instead of having to wait for a rather lengthy chemical reaction, and the range is better when comparing 1kg of battery vs 1 kg of hydrogen, with hydrogen a fair bit lighter, allowing you to fit more without weighing the car down as much (also lowering the fuel consumption since you’re physically carrying less stuff in the car).

A less talked about advantage is that there isn’t the same need for constantly replacing large, expensive batteries. If you’ve ever owned any device with a rechargeable batter (like a phone or laptop), you know they degrade quite a lot, causing them to no longer be able to hold the same charge, requiring battery replacements every couple of years, which we should probably avoid considering the environmental and social issues with mining Lithium. As stated above, batteries are still present, but they’re much smaller and won’t see the same heavy use as in vehicles that rely entirely on batteries, meaning replacements will be fewer, further apart, and with less slave labour involved.

Disadvantages

While hydrogen cars don’t produce any toxic emissions during operation, they are not exactly clean either. Hydrogen production is still considered a rather dirty process, with about 95% of hydrogen still being produced from fossil fuels.

Hydrogen cars also don’t have anywhere near the required infrastructure to support them them. Unlike battery EVs which you can just charge at home, you can’t make hydrogen at home either, so in most cases they’re quite simply a fish in the middle of the desert.

Why they won’t fix anything

First of all, it doesn’t fix the fundamental problems of individualised transport and car-centric city planning: everything is further apart, the city is loud and unsafe, and going anywhere takes several hours more than it should when the car traffic overwhelms the streets, and it will due to this little thing called induced demand: the more capacity you throw at traffic, the more people end up using cars to get places, the worse traffic gets, rinse and repeat.

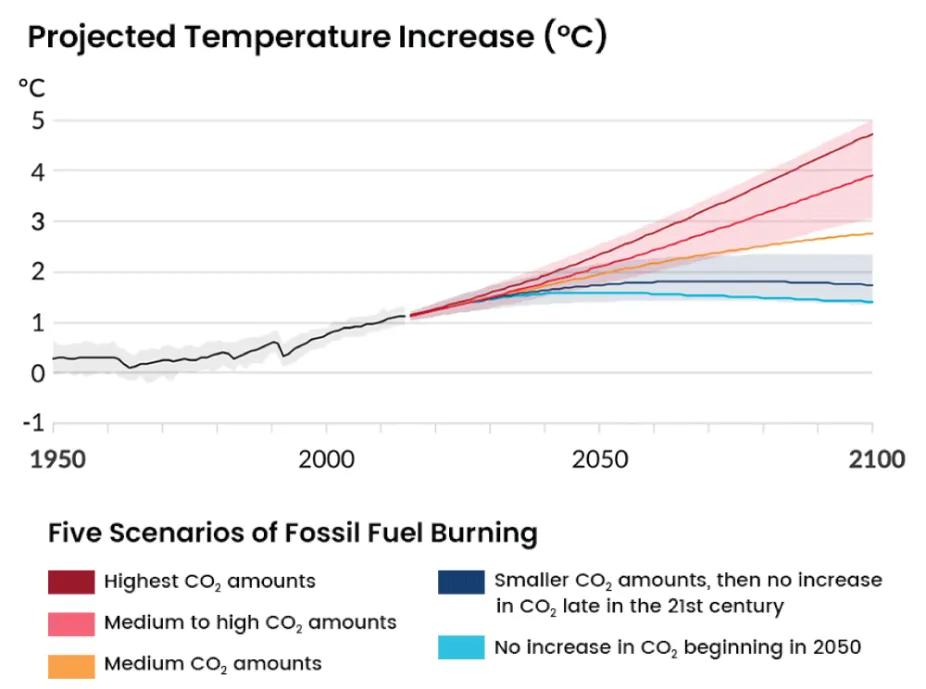

For the other massive issue, let’s start with a hypothetical. Let’s say that overnight all the infrastructure of Hydrogen cars is built, and half the city switches to them. Congrats, now half the city traffic will pump water in the air, that will be fun during heat waves! And we WILL get heat waves. Even if we go carbon neutral by 2050 (the target of most countries), we will still see higher temperatures than today for the rest of the century.

Courtesy of UCAR for the graph. source

Courtesy of UCAR for the graph. source

And I don’t know about you, but when heat waves are almost certain to be an issue for the rest of our lives, I’d rather not turn cities into massive steam cookers.

In conclusion

I don’t think the tech is necessarily bad. Hydrogen vehicles are still quite useful for things that have irregular routes like fire trucks, ambulances, or anything you can’t just predict the route of to run electric wires over. For regular, day to day transport, however, hydrogen vehicles are just another serving of the status quo, only difference being that we cooked this serving using steam instead of coal.